We live down a hill, two blocks essentially, from The Kid’s school, and something magical happens a couple of times a day when I’m at home: the sound of the bell signaling break times floats down that hill to me, followed shortly after by the sound of kids playing and yelling, their glee filling the air. I imagine TK’s voice as part of that pack, floating down to me with all the others, even though he’s not typically one of the louder ones in a group. But there was a time when he didn’t use his voice at all, and we’re not there anymore. So for me, he’s in that sound. In that music.

We live down a hill, two blocks essentially, from The Kid’s school, and something magical happens a couple of times a day when I’m at home: the sound of the bell signaling break times floats down that hill to me, followed shortly after by the sound of kids playing and yelling, their glee filling the air. I imagine TK’s voice as part of that pack, floating down to me with all the others, even though he’s not typically one of the louder ones in a group. But there was a time when he didn’t use his voice at all, and we’re not there anymore. So for me, he’s in that sound. In that music.

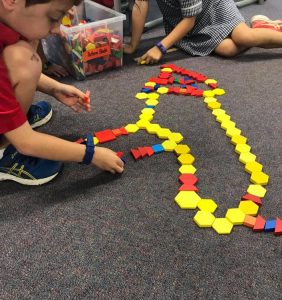

Last week I spoke to his class about apple brains and autism, and I was amazed at how attentive they were; how their rapt expressions both buoyed me and gently pushed aside my anxiousness, unlocking a path for vulnerability. For his part, TK, sitting at the front of the group on the floor along with the rest while I perched on a seat, stayed close: he kept grinning up at me and reaching for my hand, occasionally interjecting with his own comments. The kids saw him as a baby with a tilted head; they saw him in his halo after his surgery; they saw our family as it is now, four-sided and complete. They asked me questions and laughed at my jokes. They were the best audience I could have imagined, because they really listened to the story of TK. And to think, just five minutes before I had been in the car sweating through every possible pore, trying to talk myself off an anxiety ledge.

Beauty, it seems, is most often on the other side of what seems hardest.

Also last week, the day after the class talk, I headed to the school for Grandparents’ Day because, although I am not a grandparent, I get to stand in for the ones who do not live down the street or even in the same hemisphere. The year two students perform a song on their recorders every year–it’s their introduction to instruments, this plastic noisemaker, and in case you don’t remember your own version of “Hot Cross Buns” from primary school, allow me to remind you that it’s not exactly symphonic. Along with the other parents, I laughed gently and took the obligatory video (to be used years from now for bribery purposes, and certainly not to help myself fall asleep). James’s therapist had told me that he wasn’t getting the notes quite right, but that this wasn’t unusual among the group and he was front and centre anyway, which was really what I was there for. Again, as the day before: a grinning kid, looking straight at me.

The next day, the weight of the week lifting as we headed toward the weekend, I drove the boys toward their respective days and told them–something that would rarely happen on a weighted-down Monday–a few of the things I love about each of them. True to form, they barely let me name one quality before they were asking questions, wanting more. Little Brother in particular appreciated my recognition of his sense of humour and told a couple of Fozzie Bear-inspired jokes in reward for my services. His unblinking acceptance of his given and perceived role in the world, in our family, is one of the most beautiful things about our life: when we named him William (“Protector”), we had no idea all the ways that would play out, including but not limited to his recent favourite game, which involves having either me or The Husband throw a basket ball toward where TK sits in his toy car, “driving” in front of the garage, while he (LB) runs toward the ball to keep it from hitting TK. (“Let’s play ‘I Protect James,'”, he says, making me wonder if his consciousness operates on deeper levels than I can imagine.)

One of the things that stood out to a few of the kids in TK’s class was when I told them about how he often experiences sounds and light differently than many of us. It was a concrete piece of information to which they could relate, and I was grateful for how it’s been explained to me by TK–fluorescent lights, for example, that seem to pulsate to him instead of shining continuously. It’s like he’s reaching across an invisible membrane when he’s able to tell me things like this, and I can only hope that I feel the same to him, a hand reaching across to where he is, explaining my version of the world. But so often he’s the one who comes up with his own, better answers, like recently when a playground encounter involved a student bullying TK’s friend, leaving her crying. “Why did he do that?” TK asked me later, unraveled and upset as he always is when he witnesses meanness, and concerned as he always is for people who are hurting. I told him that maybe the kid was having a bad day, or that he was unhappy, which didn’t make it right for him to be mean. TK quieted and appeared thoughtful for a moment. “Or maybe he was in Demo Mode,” he offered instead.

(In Toy Story 3, while the toys are all misplaced at a day care, Buzz Lightyear is switched into Demo Mode by a bully of a toy bear, which means that Buzz’s memory is erased, which means he forgets his friends and is unkind to them.)

Just to flesh that out: my boy, whose innocence often astounds me, reasoned that another kid was being mean because of a technical glitch. When people speak of autism as a disability, I have to remember that they don’t know my son, don’t know his depthless reserves of kindness and empathy. Disabled my ass.

On Friday we met some friends at a local beach and the kids fed the seagulls while the moms drank Prosecco, and before we all dispersed to our own homes, the pack of children were naked in the ocean. Their laughter traveled across the water and sand to us, like bells down a hillside, sounds that turn into notes that become music.