The boys have been playing together so well lately, in between fights and tears over one calling the other mean, and their current top activity is creating imaginative lands full of Hot Wheels cars (The Kid) and Lion King Ooshies (Little Brother). They give these lands names and governments and citizens, and in the process give me time–to cook, or read, or just listen to them.

Every sentence seems to begin with the phrase “Just pretend” delivered as an urgent preamble: “Just pretend that there’s a bad government here and the good guys came and threw them out?!” “Just pretend that Simba ate all the hyenas and the Dodge Challenger came and picked him up?!” It’s not at all the dolls and tea parties I grew up with in my own pink bedroom but I love it. I love the imagination required to create something out of nothing, a land where one didn’t exist before. I don’t care if anything they’re saying makes sense (it doesn’t); luckily, that’s not a requirement for make believe.

It’s also not a requirement for life.

When TK was three years old, we took him to a psychologist as part of a process to have him placed in a special-needs preschool. I was biased against the whole thing from the start: it seemed we were chasing paperwork meant to categorise and define this boy of mine who defied categories and definition, and I didn’t want what was written on those pages–by people who knew him not at all–to follow him around the rest of his life. When the psychologist showed up an hour and a half late and reeking of B.O., I was almost as livid as when we received her report a few weeks later. Her appraisal of TK’s intelligence, receptive language, and capabilities were both dire and ridiculously inaccurate. I remember my exact position on our couch when I was reading it through sobs.

Now we’re chasing paperwork again, this time for a different reason–the pursuit of a second home–and The Husband and I found ourselves in another psychologist’s office last week to hear her appraisal of TK. This time the report was delivered face to face, though, without B.O. and on time, and with something else missing from the last one: humility. Or at least humility as I define it, which is not the “I’m so humbled to have five thousand Instagram followers” brand but the “I can see that I am possibly completely wrong” kind. She went on to describe the results, which–again–did not paint a promising picture. They also–given the five extra years we’ve had with TK to know him and for him to prove his ability to kick ass–were, as she admitted and due to assessment limitations, inaccurate.

Here’s a brief station break to address what often pops up at this point in people’s minds and gets cast about in furtive glances–that I am in denial about TK’s abilities, that it’s a bit sad, isn’t it, that I can’t just accept a quantitative assessment of his level of function? And I guess the answer to that, after “Fuck off unless you know him like I do, which you don’t,” would be what I’ve found over the years as life has debrided me of my need for a black-and-white, manageable, small existence, which is this: the truth about people is allowed to be complicated and layered and to not always make sense. It can’t always be neatly assessed and rendered in a purely numerical form that everyone spouting statistics is comfortable with. It’s more than that when the person is more than that.

Because the long and short of it is that there is not an assessment that has been, to date, formulated that accurately reflects the abilities of people who learn differently. Of the neurodivergent, if you will (and I will, all. day. LONG.). Which is a bit of a farce when you consider that the world is populated with all kinds of people who don’t “test well”–and as a mother who, in her day, tested fantastically, this is both hard for me to understand, and brilliantly freeing.

I am being forcibly freed of the structures and definitions I used to have in place that allowed me to define the world in a way that made sense to me. Now I have to see that world in all its messy glory and admit–humbly–that I may have been completely, utterly, wrong. And that this is a beautiful thing.

“There’s the quantitative and the qualitative,” the psychologist told us in regard to assessments, and TK, and don’t I know it: my world used to fit into formulas and now it’s painted by words, which are so much less certain and more subjective…and more poetic.

Ben Folds writes in his memoir of his early creative spark in a working-class upbringing and how easily it could have been dismissed except that his mother would not allow it. Someone suggested she take Ben to a psychologist because of the hours he would spend sitting in front of the record player–“hyper-focused and unable to cope with interruption” (sounds familiar). The psychologist assessed Ben as being developmentally challenged. His mother, in my interpretation of what Ben wrote, was all “Aww HELL no” and let him sit right there by the record player, then started him in school early. He writes, “She saw my flunking of the doctor’s test as proof of my imagination.”

He’s doing fine now, in case you were wondering.

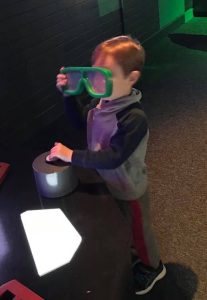

And this is how it is for those of us whose lives are demanding a bigger perspective than the safe lines of predictability: we are called to see things that others don’t, to fumble about in the darkness for what we believe is there. To walk about with this new vision we never asked for but were given anyway, the kind that sees all sorts of things that don’t make sense–but that are more real than everything that does.